Inside Out of the Shoulder

Introduction

The shoulder is a complex joint possessing a large degree of freedom that can easily break down. Familiarizing yourself with the interarticular and extraarticular supporting parts will enable you to understand the ‘why’ behind these parts. As well as why shoulder impingement syndrome and rotator cuff tears are more common than you think. This article will review the foundational anatomy and biomechanics of the shoulder, clarify the difference between shoulder impingement and rotator cuff dysfunction and teach the ‘why’ behind program design.

Learning Objectives:

1. Identify the cause of rotator cuff dysfunctions and contributing factors.

2. Identify, which exercises, are safe vs. unsafe based on biomechanics and science when working with impingement and RTC clients.

3. Identify the importance behind scapular stabilization exercises with gaining hands-on experience during the session.

4. Understand the ‘why’ behind design programs that include scapular stabilization core and functional strengthening using a multitude of exercise equipment.

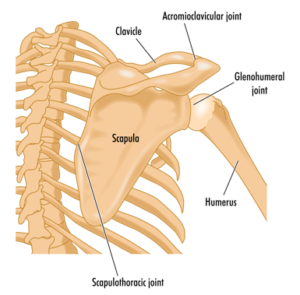

Functional anatomy

There are four primary joints within the shoulder. They include the sternoclavicular joint (SC), Which is composed of two relatively incongruent surfaces, the medial end of the clavicle and posterior lateral aspect of the manubrium and first rib. The acromioclavicular joint (AC) which is by the lateral end of the clavicle acromion. The scapulothoracic joint: is formed where the scapula articulates (meets) the thorax (upper back). Finally, the glenohumeral joint: is formed by an anterior and posterior joint capsule, ligaments that provide static stability and surrounding muscles, which can be seen in figure one.

Biomechanics of shoulder

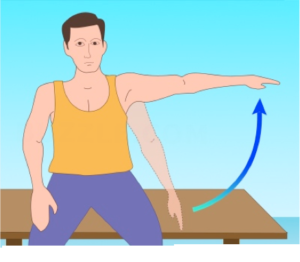

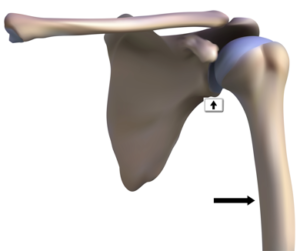

During side raising of the shoulder, the humerus slides down in the glenoid cavity(vertical arrow), while the scapula upwardly rotates on the thorax.

The upwardly rotation of the scapular on the thorax is called the scapulohumeral rhythm (SHR) as seen in figure four. Biomechanically, there is 120 degrees of movement that occurs at the glenohumeral joint and 60 degrees at the scapulothoracic joint (2:1 ratio)

Shoulder Impingement and Rotator Cuff Dysfunction

In the next section, we will review the differences between shoulder impingement and rotator cuff dysfunction.

Shoulder Impingement vs. Rotator Cuff Disease Dysfunction

Shoulder Impingement

Pathophysiology/mechanism of injury: Shoulder impingement (SI) is the mechanism in which the supraspinatus tendon of the rotator cuff becomes impinged as it passes through a narrow bony space called the sub acromial space. With repetitive movement, the supraspinatus tendon can become irritated and inflamed. SI can also be caused by a decrease in posterior capsule mobility and weakness of scapulothoracic musculature.

Evidenced based research has shown that shoulder impingement is a common condition believed to contribute to the development or progression of rotator cuff disease (Ludewig, P. 2011).

- Decrease in sub acromial space comprises the supraspinatus tendon, predisposing it

to micro tears leading to degeneration and ultimately tearing. - Tightness of the posterior capsule causes the humerus to migrate anterosuperior into

the AC joint. - Weakness of scapulothoracic muscles leads to abnormal positioning of the scapula.

Common signs and symptoms: Clients will complain typically of pain in the front of the shoulder, described as deep, dull ache with stiffness. Reaching overhead and behind one’s back will elicit pain.

Contributing risk factors: Poor posture, repetitive overhead work, and tight posterior capsule are some contributing factors. Per the research, the development of SI has been correlated to abnormal muscle activation. Specifically, those with SI, present with the overactive upper trapezius and underactive lower trapezius muscles (Chester, R., et al. 2010).

Physical therapy management:

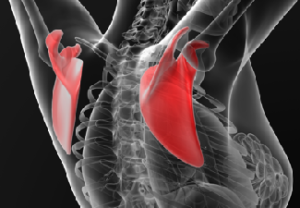

The goal with physical therapy is to restore scapular mobility, followed with stretching to restore full range of motion. Strengthening focuses on targeting the weaker upper posterior musculature that includes rhomboids, low trapezius, external rotators and serratus anterior muscles. Then patient is taught scapular stabilization and dynamic strengthening exercises.

Program design and exercise prescription for the impingement client

Once discharged from physical therapy, transitioning to the gym should be simple, and based on science, not guessing. The focus on post rehabilitation training is to strengthen the scapular stabilizers (rhomboids, low trapezius, posterior deltoid and external rotators) and posterior shoulder. Core strengthening should progress from static to dynamic exercises.

Upper body exercises that are safe based on biomechanics include:

- Low trapezius pull downs (figure 7) with cable standing or tubing, depresses and retracts the scapula, unloading the anterior shoulder, improving posture and posterior stability.

- Seated mid row (figure 8), one arm dumbbell row, seated reverse flyes

(posterior deltoid) strengthens the weaker phasic muscles of the posterior chain. - External rotation with cable, seated reverse flies, seated dumbbell side raises.

Core strengthening exercises that are safe include but not limited to; standing trunk rotation with cable/tubing, diagonal with cable tandem in place lunge, planks, planks with ball, trunk rotation with forward lunge.

Exercises that are contraindicated include with rationale:

- Seated dumbbell shoulder press (creates excessive load to the medial deltoid).

- Lat pull downs behind the head (at end or range places greatest stress on all glenohumeral ligaments as well as on the labrum).

- Upright row (at end of range-shoulder is maximally internally rotated which places stress on all glenohumeral ligaments, labrum and connective tissue).

Rotator Cuff Dysfunction

Rotator cuff disorders generally have a multifactorial etiology, including trauma, instability and degenerative changes. Ruptures of the rotator cuff have been estimated to occur in as many as 80% of individuals older than 60 years of age. Among athletes who perform repetitive overhead activities, small tears may appear later in the deterioration process as a result of secondary impingement.

Evidenced based research on rotator cuff repairs

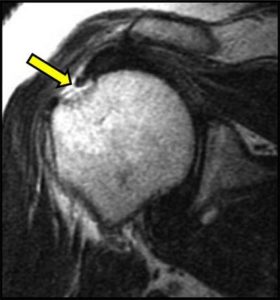

Anatomically, the supraspinatus tendon is the most commonly injured or torn muscle of the rotator cuff complex. The most common causes are mechanical impingement under the acromion, continuous micro-trauma, and degenerative changes. Because the suprapinatus tendon has a relative poor blood supply, especially at the insertion to the greater tuberosity, this results in poor healing ability (Rogers et al 2012 & Nho et al 2008).

Pathophysiology: Rotator cuff tears occur as a result of a trauma, accident or fall. Rotator cuff tears are graded from one to three in severity. They are classified as acute, chronic, degenerative, partial or full-thickness tears.

Partial thickness tears Full thickness tears

(Size: Small tears (<1 cm) Medium to large tears (2-4 cm) Large to massive (> 5 cm))

Contributing and risk factors: Charles Neer, MD, first proposed that shoulder impingement could be the best known factor for someone to develop a rotator cuff dysfunction. Shoulder impingement is defined as the inability of the humerus to glide within the glenoid cavity.

Additional factors contributing to rotator cuff tears include, degenerative changes resulting

from age, a persons lifestyle or work, tight posterior capsule which affects of the humerus spin

and rotate during both internal and external rotation of the shoulder (Yamamoto, A., et al., 2010).

Sign and symptoms: An individual who suffers a rotator cuff tear, will complain of focal, sharp, throbbing with dull ache localized pain along the medial deltoid.

Associated symptoms: Dull and deep achy pain, that occasionally throbs, and pain with sleeping on the affected side

Medical mgmt.: In the last decade, developments in imaging, particularly the MRI, have revolutionized diagnosis and management of rotator cuff disease. Indications for surgery, include failure to make progress after 4 to 6 months of conservative care, or an acute full-thickness tear in an active individual younger than 50 years of age.

Physical therapy:

The goal with physical therapy is again to first restore mobility, by the utilization of passive motion(PROM) by the therapist for six weeks to protect the surgery site. From 8 weeks post-operatively, the focus of therapy is utilizing active assistive range of motion(AAROM), followed with active range of motion.

Strengthening the posterior shoulder by targeting the external rotators, and scapular retractors (low trapezius, mid trapezius and rhomboid muscles) promotes stability throughout the shoulder complex. Typically patients will require two to three months of physical therapy to possess functional range of motion, strength and be able to independently perform common daily activities such as reaching, getting dressed, brushing their hair, before being discharged.

Recommendations for training:

Once discharged from physical therapy, transitioning from the physical therapy setting to the gym setting can be simple, however requires one important element. Knowledge. Knowing the anatomy, biomechanics of the shoulder, the type of surgery one underwent and the client’s goals are paramount before exercise prescription can despite all of this critical information, one thing remains certain. Train the client based on science not on guessing.

Exercise Prescription for the Rotator Cuff Client

The focus on post rehabilitation training is to enhance dynamic control of the scapulothoracic musculature, and strengthening the scapular stabilizers(serratus anterior, rhomboids, low trapezius and external rotators). Core strengthening should progress from static to dynamic exercises (i.e. standing in place trunk rotation with cable to traveling forward lunge with medicine ball trunk rotation).

Summary:

Shoulder impingement and rotator cuff dysfunction are common shoulder conditions that a fitness professional may encounter. Understanding the anatomy, biomechanics and proper program design with evidenced based training strategies, will provide you with a better understanding to work with clients.

References

Bernhardsson, B., et al (2012), ‘Evaluation of an exercise concept focusing on eccentric strength training of the rotator cuff for patients with sub acromial impingement syndrome, Clinical Rehabilitation, pp. 1-9.

Chester, R., et al. 2010, ‘The impact of subacromial impingement syndrome on muscle activity patterns of the shoulder complex: a systematic review of electromyographic studies’

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, vol. 11, issue 45, pp. 1-12.

Holmgren, T., 2012, ‘Effect of specific exercise strategy on need for surgery in patients with sub acromial impingement syndrome: randomized controlled study,’ British Journal of Medicine, pg. 344.

Kuhn, J., 2009, ‘Exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff impingement: A systematic review and a synthesized evidence-based rehabilitation protocol,’ Journal of Shoulder Elbow Surgery, vol. 18, pp. 38-160.

Ludewig, P., 2011, ‘Shoulder Impingement: Biomechanical Considerations in Rehabilitation,’

Journal of Manual Therapy, vol. 16, issue, pp. 33–39.

Chris Gellert, PT, MMusc & Sportsphysio, MPT, CSCS, C-IASTM, CPC

Chris is the CEO of Pinnacle Training & Consulting Systems(PTCS). A continuing education company that provides educational material in the forms of evidenced based home study courses, ELearning courses, live seminars, DVDs, webinars, articles and teaching in-depth, the foundation science, functional assessments and practical application behind Human Movement. Chris is both a dynamic physical therapist with 19 years experience, and a personal trainer with 20 years experience, with advanced training, has created 16 home study courses, is an experienced international fitness presenter, writes for various websites and international publications, consults and teaches seminars on human movement. For more information, please visit www.pinnacle–tcs.com.